Pellucid Marginal Degeneration Pentacam vs. Keratoconus

When it comes to corneal diseases, two of the most frequently misunderstood and misdiagnosed conditions are Pellucid Marginal Degeneration, Pentacam, and Keratoconus (KC). Both are classified as ectatic corneal disorders, meaning they involve thinning and abnormal protrusion of the cornea. While PMD and keratoconus share overlapping clinical features—such as progressive irregular astigmatism, distorted vision, and challenges with contact lens fitting—they differ in their patterns of thinning, age of onset, and long-term prognosis.

Understanding these differences is crucial for obtaining an accurate diagnosis, as treatment strategies vary depending on whether the corneal thinning primarily affects the inferior periphery (as in PMD) or the central/paracentral cornea (as in keratoconus). In this blog, we’ll explore the similarities and differences between these two ectatic diseases, discuss the role of advanced imaging such as corneal topography and Pentacam, and outline the treatment options available today.

Introduction to Ectatic Corneal Diseases

Ectatic disorders, such as pellucid marginal degeneration and keratoconus, involve the structural weakening of the cornea, leading to progressive deformation and visual decline. These conditions alter the corneal shape, resulting in irregular astigmatism, against-the-rule astigmatism, and loss of visual acuity.

- Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD): A relatively rare disorder characterized by inferior corneal thinning near the limbus. The inferior periphery of the cornea loses its normal thickness while the central cornea remains largely unaffected. This unique feature often preserves the normal thickness centrally but causes severe refractive errors.

- Keratoconus (KC): Far more common, KC involves progressive thinning of the central or paracentral cornea. This leads to a conical protrusion, scarring, and sometimes acute complications such as corneal hydrops.

Both conditions are categorized as corneal ectasias, but their clinical pictures differ significantly. Tools such as corneal topography, tomography, and posterior elevation data from devices like the Pentacam are indispensable for distinguishing these disorders.

Understanding Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD)

Pellucid Marginal Corneal Degeneration is marked by a crescent-shaped band of thinning along the inferior peripheral cornea, usually 1–2 mm from the inferior limbus. This thinning typically spares the central cornea, which is why patients may present with severe astigmatism yet minimal central scarring.

Key clinical findings include:

- Thinning in the inferior periphery, usually spanning 4–8 o’clock.

- Preservation of the central cornea and the superior corneal tissue.

- Corneal protrusion just above the thinning zone, creating irregular curvature.

- Distinctive crab claw pattern or claw-shaped pattern on corneal topography, reflecting inferior steepening and superior flattening.

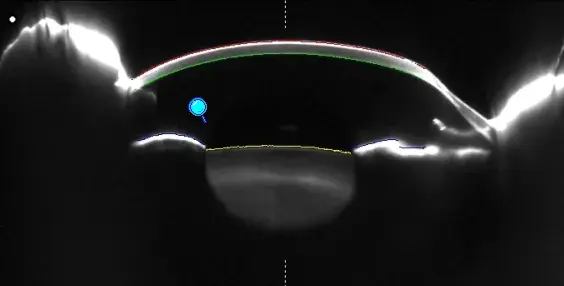

Early Pellucid Marginal Degeneration may be difficult to detect, as patients present with slowly progressive astigmatism. Advanced imaging, including Scheimpflug imaging and anterior eye OCT, is essential to capture the thinning profile.

Although the exact cause remains unclear, genetics, collagen abnormalities, and possibly mechanical stress are contributing factors. Unlike keratoconus, PMD rarely leads to lipid deposition or central scarring. However, in advanced cases, patients may need surgical intervention.

Understanding Keratoconus (KC)

Keratoconus is the most common ectatic disorder, affecting both eyes in most cases. It typically begins in adolescence or early adulthood and progresses throughout the 20s and 30s. Unlike PMD, thinning involves the central or paracentral cornea, resulting in a cone-shaped protrusion.

Clinical picture:

- Irregular corneal shape with cone-like protrusion.

- Significant irregular astigmatism, progressive myopia, and reduced visual acuity.

- Paracentral corneal thinning on pachymetry scans.

- Risk of corneal vascularization, hydrops, and scarring in advanced disease.

Risk factors include:

- Genetic predisposition.

- Chronic eye rubbing.

- Connective tissue disorders.

- Environmental influences, such as allergies.

Unlike PMD, keratoconus is more prevalent and often progresses more rapidly, sometimes requiring early corneal collagen cross-linking to stabilize the corneal tissue.

Corneal Topography and Diagnostic Evaluation

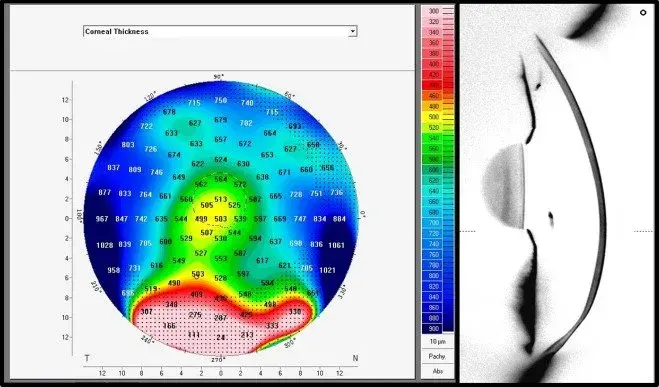

One of the most valuable diagnostic tools in differentiating these ectatic diseases is corneal topography. Advanced devices such as the Pentacam generate a 3D map of the anterior corneal surface, posterior elevation, and corneal thickness profile.

Topographic findings include:

- PMD: A distinctive “crab claw” or “beer belly” pattern, with steepening superior to the thinning zone.

- Keratoconus: A classic inferior steepening within the central or paracentral cornea.

To ensure proper diagnosis, clinicians also rely on:

- Pachymetry maps to measure corneal thickness across the entire cornea.

- Elevation data to detect early signs of protrusion.

- Slit-lamp examination to assess for scarring, lipid deposition, or secondary complications.

A combination of clinical findings, patient history, and advanced imaging ensures accurate differentiation between pellucid marginal degeneration, inferior keratoconus, and other related thinning disorders.

Clinical Differentiation: PMD vs. Keratoconus

Here’s how PMD and KC differ in presentation:

-

Location of thinning

- PMD: Inferior peripheral cornea, typically sparing the central area.

- KC: Central or paracentral cornea, involving the visual axis.

-

Topography

- PMD: Crab claw pattern, often mistaken for keratoconus.

- KC: Localized inferior steepening within the cone.

-

Age of onset

- PMD: Diagnosed later, often in the 20s or 30s.

- KC: Diagnosed earlier, often in teenage years.

-

Complications

- PMD: Rarely causes central scarring but can still result in severe astigmatism.

- KC: More likely to cause scarring, corneal hydrops, and vision loss.

Correct identification of these differences is critical in designing treatment strategies. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate refractive surgery, which may worsen ectasia.

Treatment Options for Pellucid Marginal Degeneration & Keratoconus

Management strategies for ectatic corneal diseases must be carefully individualized, as the approach depends on the severity of thinning, the location of the abnormality, and the patient’s visual needs. Both pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD) and keratoconus can often be managed conservatively in the early stages, but advanced cases may require surgical procedures.

Non-surgical treatments

-

Contact lenses:

- Scleral lenses and hybrid lenses are often the first line of treatment for patients with irregular astigmatism. By vaulting over the inferior cornea and creating a smooth refractive surface, they restore functional vision and provide excellent comfort.

- Specialty contact lenses remain particularly effective in the early stages of PMD and KC, often delaying the need for invasive interventions.

- Conventional glasses can correct mild refractive error but are inadequate once peripheral thinning and corneal distortion increase.

Surgical and advanced treatments

-

Corneal Collagen Cross Linking (CXL)

- This procedure uses riboflavin and UVA irradiation to stiffen the corneal collagen fibers, halting the progression of corneal ectasias.

- CXL is especially valuable in early pellucid marginal degeneration and keratoconus, offering stabilization before severe damage occurs.

-

Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS)

- An advanced treatment option where donor corneal tissue segments are implanted to regularize corneal curvature.

- CAIRS has gained preference over older synthetic implants, such as Intacs, due to its improved biocompatibility and better outcomes.

- It is particularly effective in unilateral pellucid marginal degeneration, where thinning along the vertical meridian can severely distort the visual axis.

-

Intracorneal ring implants

- Synthetic arcs are inserted into the corneal tissue to flatten steep areas and improve corneal symmetry.

- These are best suited for carefully selected cases where thinning is not too advanced.

-

Keratoplasty (Corneal Transplantation)

- Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty (DALK) and Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK) remain options for advanced cases with severe scarring or vision loss.

- PK replaces the full corneal thickness, whereas DALK preserves healthy endothelium, reducing the risk of rejection.

- Both are considered surgical procedures of last resort, but they can restore vision when other options fail.

Important note: Refractive surgery such as LASIK or PRK is contraindicated in both PMD and keratoconus. Multiple studies—including those cited in J Cataract and Cataract Refract Surg—have highlighted the danger of worsening ectasia after these procedures.

Prognosis, Complications & Future Directions

The prognosis of PMD and keratoconus depends on timely diagnosis and access to modern treatments. Without intervention, patients face progressive peripheral thinning, severe irregular corneal shape, and complications such as:

- Rapidly worsening astigmatism with reduced visual acuity.

- Development of corneal hydrops or scarring.

- Increased risk of requiring penetrating keratoplasty in advanced stages.

- Potential for vision loss, which can impact daily function and independence.

Encouragingly, recent advances in ophthalmology and visual sciences—including collagen cross-linking, CAIRS, and advanced scleral lens fitting—allow many patients to maintain useful vision and avoid transplantation.

Researchers are also investigating:

- Biologic implants to reinforce the corneal tissue.

- Gene therapies targeting collagen abnormalities.

- Improved imaging, such as enhanced Pentacam elevation data, enables the detection of early pellucid marginal degeneration before visual damage becomes significant.

- Associations between ectatic corneal disease and other conditions, such as retinal lattice degeneration, may inform comprehensive patient care in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, while pellucid marginal degeneration and keratoconus share features of progressive corneal thinning, they diverge in their clinical picture, anatomical location, and risks. PMD is typically associated with thinning along the inferior periphery and a classic crab claw pattern on topography, whereas keratoconus affects the central/paracentral cornea and often progresses earlier.

Accurate differentiation is crucial. Using corneal topography, Pentacam imaging, slit lamp examination, and pachymetry maps, ophthalmologists can distinguish PMD from inferior keratoconus and other related thinning disorders. This ensures that patients avoid unsafe refractive surgery and instead benefit from effective strategies such as corneal collagen cross-linking, CAIRS, or specialty contact lenses.

Ultimately, early detection, personalized treatment, and careful monitoring improve outcomes and reduce the likelihood of requiring surgical procedures, such as transplantation. With continued innovation and research, patients with PMD or keratoconus have more hope than ever for preserving their sight and quality of life.