Keratoconus vs. Keratoglobus | Understanding Corneal Eye Conditions — DR BRENDAN CRONIN OPHTHALMOLOGIST

Introduction: Keratoconus vs. Keratoglobus

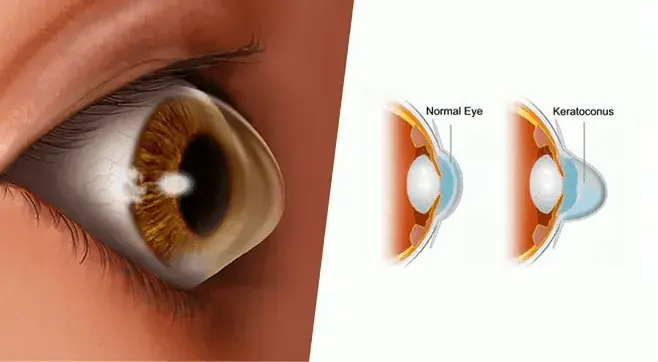

Two conditions that often confuse patients and even general practitioners because of their similar names are keratoconus and keratoglobus. Both are classified as corneal ectasias, meaning diseases where the cornea becomes abnormally thin and distorted. These conditions disrupt the normal, transparent, dome-like shape of the cornea, causing light to scatter as it enters the eye and thereby reducing vision quality.

While keratoconus is a relatively common disorder, keratoglobus is considered a rarer condition. The difference lies not only in the patterns of corneal thinning but also in the severity of complications, management options, and surgical strategies. Understanding these distinctions is essential for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and improving the best corrected visual acuity of affected patients.

Clinical Findings and Ocular Signs

The ocular signs of keratoconus and keratoglobus can overlap, but they also present distinct features that guide ophthalmologists in diagnosis.

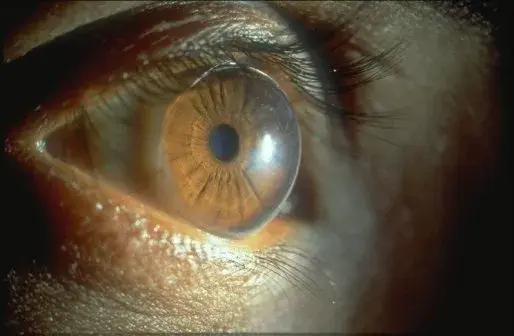

In keratoconus, patients typically present in their teens or early adulthood with increasing blurred vision, irregular astigmatism, and frequent changes in their spectacle prescription. Examination often reveals a conical protrusion of the cornea, thinning at the apex, and distortion of the K values on corneal topography. Fleischer’s ring, Vogt’s striae, and scissoring reflex on retinoscopy are hallmark findings.

In contrast, keratoglobus involves more generalized and diffuse thinning across the entire cornea, characterized by a globular protrusion rather than a cone. Because of the thin cornea, these patients are at higher risk of corneal perforation even after trivial trauma or minimal trauma, making protective glasses a crucial part of management. Additional findings may include blue sclera, bilateral keratoglobus, and associated connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome.

Both diseases can lead to high myopia, irregular astigmatism, and reduced vision that does not fully correct with glasses. Many patients require contact lens insertion, often with a scleral contact lens, to achieve functional refractive correction.

Corneal Shape and Corneal Thinning in Both Conditions

The shape of the cornea is the most obvious clinical difference between the two disorders.

Keratoconus:

Localized thinning results in a cone-shaped protrusion of the cornea, typically located inferiorly or centrally. This irregular curvature produces progressive visual distortion, glare, and image ghosting. Over time, the disease stabilizes, but some patients progress rapidly and require early surgical management.

Keratoglobus:

Instead of a cone, the entire cornea becomes thin and takes on a rounded or globular protrusion. The extreme thinning makes the cornea fragile, increasing the risk of rupture and acute corneal hydrops. Unlike keratoconus, this condition is often present from birth or early childhood and may be associated with acquired keratoglobus in later life following chronic inflammatory disease.

In both cases, corneal topography plays a vital role in diagnosis and monitoring disease progression. Precise mapping of the corneal curvature helps ophthalmologists decide between conservative treatment, new surgical techniques, or more traditional surgical procedures such as penetrating keratoplasty.

Progression, Risk Factors, and Associated Conditions

Keratoconus usually appears in adolescence and progresses over 10–20 years before stabilizing. Risk factors include eye rubbing, family history, and associated systemic or ocular conditions. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is strongly associated, as persistent eye rubbing and chronic inflammation accelerate corneal weakening. Similarly, chronic marginal blepharitis and poorly managed allergic eye disease can worsen corneal thinning.

Keratoglobus, however, is less predictable. It often manifests early in life and may progress slowly, but carries a higher risk of complications such as corneal perforation. Some patients develop acquired keratoglobus in adulthood as a result of inflammatory disorders. Systemic connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and blue sclera syndrome, are often linked with bilateral presentation.

Both diseases carry the risk of glaucoma, retinal detachment, and reduced best corrected visual acuity if left unmanaged. Case reports in leading journals, such as the British Journal of Ophthalmology and Archives of Ophthalmology, have documented severe cases of bilateral disease, acute hydrops, and even vision loss in one eye or the same patient, affecting the left eye and right eye at different times.

Acute Hydrops and Complications

One of the most feared complications in corneal ectasias is acute hydrops. This occurs when Descemet’s membrane ruptures, allowing fluid from the anterior chamber to flood into the cornea. The result is sudden, painful swelling, dramatic loss of vision, and prolonged resolution time that can extend to weeks or months.

In keratoconus, acute hydrops may occur spontaneously, but it is less common. In keratoglobus, due to the thin cornea and diffuse thinning, the risk is significantly higher, sometimes triggered by even trivial trauma. The disease can lead to recurrent hydrops, corneal scarring, and a permanent reduction in best-corrected visual acuity.

Management often includes bandage contact lenses, hypertonic saline, and, in some cases, intracameral injection of perfluoropropane gas to accelerate recovery. However, in keratoglobus patients, surgical repair may be needed due to extreme thinning.

Management Options and Conservative Therapy

When considering management options, ophthalmologists take into account the severity of the disease, the patient’s age, and the risk of complications. Conservative approaches remain the first step in many cases.

Conservative Therapy Includes:

- Glasses or Contact Lenses: Early disease can often be managed with glasses, but advanced cases usually require scleral contact lenses or rigid gas-permeable lenses for refractive correction.

- Protective Glasses: Recommended for keratoglobus patients to prevent minimal trauma that may cause perforation.

- Bandage Contact Lens: Provides comfort in cases of acute hydrops or minor surface damage.

- Follow-up and Monitoring: Regular eye examinations, corneal imaging, and tracking of K values are essential.

- Conservative Therapy for Associated Conditions: Treating vernal keratoconjunctivitis, chronic marginal blepharitis, and allergies to reduce the risk of progression.

Surgical Procedures and New Surgical Techniques

When conservative methods fail or complications arise, surgical management is required. Ophthalmologists now have access to various surgical procedures and alternative surgical procedures designed to stabilize and restore corneal function.

Key Surgical Options:

- Collagen Cross-Linking (CXL): Strengthens the cornea in keratoconus but is rarely suitable for keratoglobus due to extreme thinning.

- CAIRS (Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments): A new surgical technique for keratoconus, offering stability with minimal risk.

- Peripheral Intralamellar Tuck: Helps manage diffuse thinning in keratoglobus, improving stability with less minimal trauma risk.

- Penetrating Keratoplasty: Full-thickness corneal transplantation for advanced ectasia or perforation.

- Central Lamellar Keratoplasty: Preserves corneal integrity while addressing localized thinning.

- Alternative Surgical Procedure Trials: As reported by researchers such as Shah S, Tandon R, and colleagues at Prasad Eye Institute, modified keratoplasty and intrastromal techniques continue to evolve.

- Intracameral Perfluoropropane Gas: Used in select cases to manage acute hydrops and reduce resolution time.

Each procedure carries risks, including graft rejection, intraocular pressure spikes, or even retinal detachment, underscoring the importance of tailoring surgical strategy to each patient’s condition.

Keratoconus and Keratoglobus – Diagnosis and Treatment Outlook

Although keratoconus and keratoglobus share overlapping features, they remain distinct conditions with unique diagnostic challenges and treatment pathways. Keratoconus is more prevalent, with well-established therapies including corneal cross-linking and scleral contact lens fitting. Keratoglobus, being a rarer condition, demands heightened caution due to its extreme thinning, higher risk of corneal perforation, and limited options for safe surgical correction.

Recent studies in Arch Ophthalmol, Br J Ophthalmol, and institutional reports from Prasad Eye Institute highlight ongoing research into new surgical techniques, improved surgical management, and safer alternative surgical procedures for these complex diseases.

For patients, the key lies in early diagnosis, regular follow-up, and individualized management options tailored to their specific needs. For ophthalmologists, the challenge remains in balancing conservative therapy with advanced surgical procedures and minimizing risks, such as glaucoma, retinal detachment, and graft failure.

Ultimately, understanding the differences between these two corneal ectasias ensures better treatment, improved vision, and greater quality of life for patients. As research continues, novel interventions promise safer and more effective ways to manage both keratoconus and keratoglobus in the future.